Bubble Trouble: Why Should You Care About Corporate Debt?

How Corporate Defaults Could Affect Your Portfolio

Corporate debt is one of those words that makes most people start to tune out. It sounds like a banker-type term that doesn’t apply to everyday investors, but to assume this would be incorrect. Financial markets are interconnected, and any significant event or trend that takes place in one affects the others. Meanwhile, events that happen in financial markets trickle down to affect the entire economy. This means lots of events that retail investors might not be aware of are often the catalysts that end up affecting their salaries, mortgages, and so on. And while there isn’t much that Main Streeters can do to change certain situations, there are steps they can take to limit their exposure in the event that they take care to be informed. Multiple factors affect markets at any given time, but outliers – such as record highs of any kind – often have the potential to have much greater impact in the event that they don’t pan out as planned.

Buybacks, Cheap Debt, and Record Highs: Why Today’s Corporate Debt Market is Unique

Corporate debt, firstly, is similar to any other debt – except it’s generated by bonds offered by a company that are sold to willing investors. These investors, essentially, are loaning the company their money in return for something that functions much like an IOU. Bonds are different from stocks in that stocks are technically an ownership share in the company, complete with all the risks involved regarding whether the business succeeds or fails, while bonds are simply loans that are promised to be repaid in the future at their principal amount with interest. Because of this, bonds have historically been considered safer investments than stocks. However, while in the past, corporate bonds were typically issued to fund business investments – like research and design, acquisitions that would better position a company for growth, or hiring more workers to keep up with growing demand – many of today’s corporate debt issuances are used to fund stock buybacks rather than bolster the business economy, putting their ability to pay back those bonds at risk. Meanwhile, corporate debt is at a record high. After the recession in 2008, the Federal Reserve dropped interest rates to record lows in hopes of stimulating the economy. Low interest rates means cheap debt – in other words, the ability to borrow money at only one percent interest versus four. Businesses loaded up on cheap debt, and while the amount of corporate debt was hovering just around six trillion before the Great Recession, today it stands at a record high of $13.5 trillion. This figure is more than double the amount before the downturn and represents a little more than 64 percent of the United States’ GDP. In addition, while the amount of debt has increased, the quality of that debt has drastically decreased.

Bond Ratings: Is It Junk?

Corporate bonds are given investment grades by ratings agencies, like Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s, so that investors can get a sense of the amount of risk they’ll be taking on when loaning out their money. Riskier bonds get higher payouts in the form of higher interest rates, while more secure bonds have lower returns. Divided into two main categories, bonds can be classified as either “investment grade” or “junk.” In the investment grade category, bonds have ratings that range from AAA to BBB – with BBB being the lowest rating possible to still be considered investment grade. From 2000 to 2007, around 39 percent of corporate bonds were BBB. Today, that percentage stands at over 51 percent. Anything below BBB, meanwhile, is considered junk – also known as high-yield or speculative bonds. Junk bonds, with lower liquidity, have less ability to pay back their bonds on short notice. And similar to the overall corporate debt market, junk bonds have also almost doubled since 2007, growing from around $700 billion to $1.2 trillion, or around 25 percent of all corporate bonds. In total, a little under a quarter of the entire bond market today is highly rated. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in a 2019 report, has emphasized that, “Compared with previous credit cycles, today’s stock of outstanding corporate bonds has lower overall credit quality, higher payback requirements, longer maturities and inferior covenant protection.”

If corporate bonds default, so what?

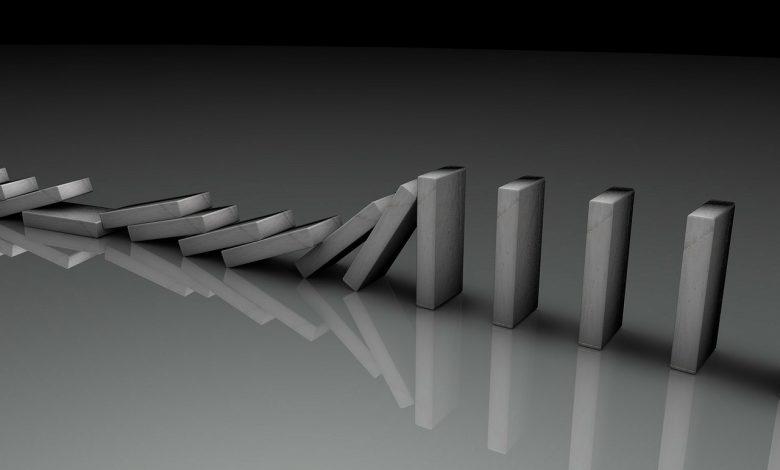

While the increases may not seem like much on paper, in the second quarter of 2008, the U.S. recession started gaining steam with delinquencies that stood at just 4.5 percent of all mortgages at the time. A snowball effect occurred as reduced credit ratings and lessened liquidity affected banks and other parts of the financial system. Likewise, in the event that a company with corporate debt can’t repay its loans, it has a knock-on effect on other financial markets. An economic downturn – or higher interest rates, about which there has been much ado in the last two years – could cause highly leveraged companies to find servicing their debt significantly more difficult. When default rates increase, bond ratings are subsequently downgraded, and fixed-income investors (such those managing pension funds) are obligated by law to liquidate any substantial holdings that fall below investment grade. This is called forced selling, and it can create substantial price drops, as well as flood the market with bonds for which there may or may not be buyers. Liquidity crunches in the bond market, meanwhile, can have similar significant impact on the markets and entities connected to it, including the stock market and banks. Just like homebuyers with unaffordable mortgages ultimately affect the larger economy when those loans come due and subsequently default, corporate debt has an effect on the economy as well in the event those corporate loans go sour.

In financial markets, it’s difficult, sometimes impossible, to keep track of everything that goes on behind the scenes. But the characteristics of some of these underlying fundamentals are sometimes the catalysts that cause events that have ripple effects on retail investors – those with retirement money in a pension fund, large sums invested in stock, or even a family business that’s depending on a flourishing economy and good business conditions. While the market may go up over time, it’s never a bad idea to keep one finger on the pulse of the underlying market conditions that could ultimately also affect your own investments.